The following article was written by the late Bob Whitehead when he was an associate editor at "Old Motor" during his spare time. The article was published in Old Motor, Volume 9, Issue 1 in 1975.

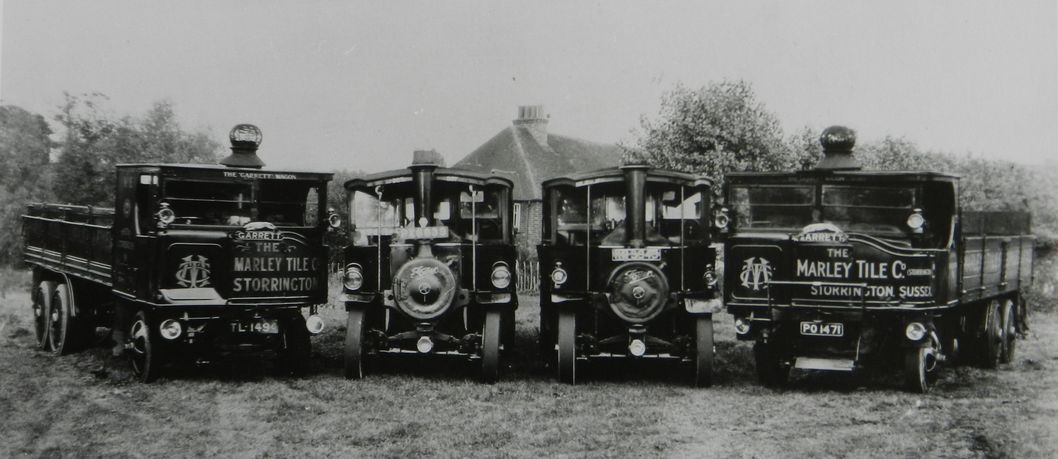

THE MARLEY TILE FLEET

From tiny beginnings as builders, Marley grew to a mammoth company with the highest paid chairman in Britain. BOB WHITEHEAD has been looking at the transport which contributed to this remarkable success story.

OWEN Aisher Senior, born in 1876, began his working life as a plasterer but, having joined the army in the Boer War, he stayed with it until 1919 when he left it to live in Charing Heath, Kent, from which base he Intended to develop some building land he had bought at nearby Harrietsham. Here, with a partner, Arthur Blackman, a local coach merchant, he built and sold bungalows and in the workshop he established for the purposes of this small building business he began to make doors, windows and similar joinery for sale to other local builders. Scarcity of clay roofing tiles and the poor quality of machine-made clay tiles caused him to become interested ln the hand-operated machines developed by Winget Limited of Rochester, for making concrete tiles from a mixture of Portland cement and selected sands. His tile making activities from one of these machines, intended initially to meet the needs of its own firm, were soon expanded to supply an increasing circle of customers in the district. The possibilities of this trade so engaged the attention of his eldest son, Owen Junior, that in 1924, at the age of twenty-three, he resigned his post as a London policeman and joined his father in the business of supplying and fixing concrete roof tiling, which was the foundation of the present Marley activities.

The trade name Marley seems to have been selected more or less at random and was the surname of a well-known Kentish family closely associated with Harrietsham.

For fetching in the sand to this small tile works, Owen Aisher bought an ex war department Foden five ton steam wagon, works No 7820 (FY 2141), built in January 1918. He was its fourth owner and after it had served him for a year or two he sold it, in turn, to C J R Fyson & Son of Soham, Cambridgeshire. Writing of those early days Jack Aisher, the youngest son, said, “Progress was not dramatic but by 1928 we had three works at Harrietsham, Storrington in Sussex and Leighton Buzzard in Bedfordshire.” The factory at Riverhead, near Sevenoaks, Kent, the present headquarters, was opened in 1935 followed by Aveley and Burton-on-Trent. Because of this growth, FY 2141 was followed by two new Foden solid tyred six tonners (12262 and 12334 - KM 5943 and KM 7647) which were, so to speak, the founding fathers of the Marley Tile Works fleet. These were subsequently converted to pneumatics. Four other Fodens followed (Nos 12654, 12748 and 12846 - which were ‘flexible', i.e. articulated six wheelers) and 13356 an E-class vertical boilered six wheeler undertype. The artics had a good platform area, useful for easy loading and unloading but, in common with many articulated vehicles - and not only vintage examples - they had braking problems when empty. Marley drivers were expected to get in a pretty full day's mileage and consequently tended to push on with some enthusiasm when unladen, with the result that several incidents occurred of total or partial jack-knifing.

The final dawning of disillusion concerning articulated six-wheelers, after experiences during the 1927-28 winter, seems to have coincided with a visit to Harrietsham by the late Frank Wall, the gifted salesman in Kent and Sussex of Richard Garrett & Sons Ltd. Coincidence may not have been the only factor involved as Frank had a very keen ear and calculation or acute observation may have been significant ingredients. In consequence of this and succeeding visits, Marley acquired during 1928 and '29 eight six-wheeled Garrett undertypes. Slightly later they bought, in 1931, two second-hand six-wheelers and, in 1932 No 35473, the pioneer Garrett four-wheeler on giant pneumatics. In addition to these wagons used on deliveries, the works had various petrol-engined lorries used for odd jobs. The first of these, of which no details survive, was an ex WD Peerless chain-drive on wooden wheels with solids. This was more or less contemporary with FY 2141. Its successor was a 4/5 ton AEC normal control four-wheeler of which, again, virtually no details survive. The driver of this vehicle, an elderly man, left work at Harrietsham at midday one hot summer Saturday and set off homewards on his cycle over the chalk hills to the north of Harrietsham. On his way he stopped for refreshment at a pub and having‚ perhaps, consumed more beer than discretion would have dictated, lost control of his cycle on a steep gradient fell off and killed himself. So hard were the times that a young man named Albert Kite, hearing of the accident, immediately cycled to Harrietsham, applied for the job thus rendered vacant, and began work on the Monday.

His first encounter with the senior partner happened about two hours after he had started work. As he related, the old gentleman “came across the field tilting his hat forward to shade his eyes” - always a danger signal as he subsequently learned. Albert had taken the sides off the bonnet of the old AEC to size up his problems, so to speak, when Aisher Senior positioned himself behind him, glaring belligerently at the state of the engine. “When did you last clean that, mate?“ he demanded, and no amount of protest about Albert's short time with the firm saved him from a severe wigging. Notwithstanding that. He went on to work for Marley for another forty-four years.

Another early treasure was a light flat lorry built on the chassis of an ex Southdown Dennis coach. Being light and on pneumatics and having slightly higher gear ratios. this was fairly fast, but its downfall was the excess of its apparent over its actual load-carrying capacity, which led to its being over-loaded and consequently to tyre trouble.

The slump and the changed taxation rules of 1933 killed off the Marley steamers. The Aishers were faced with much increased road tax at a time when contract hauliers were ten a penny. Consequently they decided to sell of their steam fleet and sub-contracted all their delivery haulage for the next two years. Blackman was still a partner at this time, though he took no part in the actual management, and had become somewhat alarmed at the headlong pace of expansion.

In 1934, however, he withdrew, his original £4000 share having increased to £300,000 in value. Had he elected to stay in he would have seen it grow, by 1974, to £30M. The firm was reconstituted as The Marley Tile (Holding) Company Ltd, afterwards renamed Marley Ltd, and shortly afterwards, moved to the present headquarters at Riverhead, situated on an aggregate source on the banks of the River Darenth and designed to service the great South London suburban expansion of the late thirties.

Though haulage by contract had had advantages in theory from the point of view of the manufacturing company, the actual performance of the hauliers had proved to be less reliable than directly owned transport. The decision was taken, therefore, to form a family-owned haulage company which, it was calculated, would continue the advantages of a contract haulage situation to the parent company whilst abolishing the disadvantages occasioned by the vagaries of contractors. with the further advantage that the profits. If any. arising would remain with the family. Consequently, in late 1934 steps were taken to set up a company known as Tile Haulage Ltd. which began to trade the following year from a head office in Smith Square, London SW1 using three eight-wheeled, oil-engined AEC Mammoth Majors. From the initial three, the number of Mammoth Majors had increased to twenty-five at the outbreak of war in 1939.

One further development occurred before the outbreak of war. ln 1938 the old established North Kent haulage firm of Martin & Sillett of Barnetts Road, Strood, went into liquidation. lt was purchased and renamed Martin & Sillett (1938) Ltd, absorbed the Tile Haulage fleet, taking over the haulage work of the group. In 1969 to emphasise its affiliation it was retitled Marley Transport Ltd.

Three of the Mammoth Majors ran until 1965, a total of thirty years service during which their individual mileages each approached the million mark. Even then the twin factors which settled their respective fates were decreasing availability of spares and the spartan comfort, by 1965 standards, of their cabs. The firm were not, however, totally faithful to the marque in pre-war days. In the late thirties, in the true spirit of experiment, they purchased a Gilford HSG with gas producer equipment, which ran until 1951, albeit latterly converted to a Gardner oil engine. When I discussed this, in April 1974, with Vic Dugay, the manager of Marley Transport, the baffling vagaries of this intriguing vehicle were as fresh in his mind as they were thirty years before. One day it would perform impeccably, pulling well and climbing hills as well as an oiler. The next day, serviced and fuelled in an apparently identical manner, it would sulk and jib like a temperamental horse. Thus on a good day it would leave the works and almost soar over Polhill on the road to London, whereas the next it would be all the driver could do to coax it over the top. What subtleties of fuel composition or atmospheric conditions conspired to produce these tantrums were never discovered, despite the effort and hours of debate and experiment devoted to the investigation. There were also two Thornycroft normal control artics dating from the mid-thirties. These two vehicles were pathetically underpowered. I remember one of them being engaged, in 1938. in hauling broken tiles from Riverhead to Sevenoaks railway goods yard. There would be a loud roaring as it charged down the slope from Brittains Lane to the Halfway House in the hope of getting as far as possible up the rise to the goods yard gate by the momentum thus gained. Usually not enough was picked up and the sound would end in a series of near stalls, punctuated by bursts of high engine revs as the driver dropped frantically through the gears in an effort to avoid coming to a stand. It was with one of these tired horses, whilst on the dust-run (collecting cement from Snodland), that Albert Kite whilst trying to gain downhill some of the time he had lost uphill came upon an unexpectedly icy road, touched the brakes and had the semi-trailer jack-knife upon him. Soon afterwards both Thornycrofts disappeared.

The outbreak of war led to a rapid run-down in tile sales and consequently in the haulage fleet, which dropped to three Mammoth Majors. For a time even these were on hire to the Ministry of War Transport. At the end of the war, and thus outside the real scope of this article, they were augmented by some International K8's, brought over under Lend Lease and by some Leyland Beaver Six and Octopus chassis, followed in 1948 by Maudslay Meritors and Mustangs, part of a frustrated export. These latter were a story in themselves which is too long to be told here.

Of the vehicles hired by the company during its fifty years few are remembered. Probably the most interesting incident came as a result of the last fling of the enemy against London and the suburbs when flying bombs and rockets destroyed the roofs of thousands of homes and roofing tiles suddenly came into great demand when the company was desperately short of transport, and fuel was severely rationed. To help over this period a Sentinel S8. owned at the time by Burrows, the Maidstone builders and haulage contractors, was hired. For some while in 1945 and '46 it worked in and out of Riverhead but was displaced by the arrival of the Internationals and was lost to my view. I never found out what happened to it.

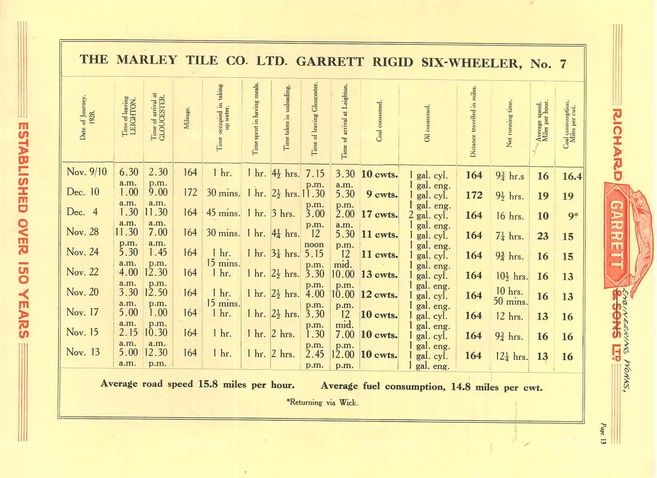

Life in the Marley transport fleet was always strenuous but always rewarding because of the tremendous spirit of identity that prevailed. Men, like Albert Kite, who joined in the thirties, often stayed for the remainder of their working lives. Just how demanding the life of a steam wagon crew was, is illustrated by the log of Marley's Garrett six-wheeler No 7 (Works No 35199), preserved in a letter its owners wrote to the makers. It is interesting to note how the mileage per hundredweight of coal fell progressively but rose again on 10th December, perhaps upon the renewal of the superheater tubes, always a weak point. All this apart, however, what hours the crews worked, mechanical troubles on the road were generally dealt with on the spot. If the driver, whether of a steamer or a diesel, could limp on under a jury rig he was expected to. The first question from base when a driver phoned in to report a breakdown was always "Have you delivered the load?" The next. and reassuring comment. Was equally inevitable - “Stay with it and I’ll be out to you." If a driver had run a big-end it was taken for granted that he would have dropped the sump and dismantled the bearing by the time the fitter got to him. He would help with the repair and, if the load was still on, go on to deliver that before returning to the depot. The situation of a vehicle had to be desperate before a tow-in was considered. The personal self-reliance and independence upon which this depended was sustained by a spirit of mutual regard that permeated the firm - known to Australians as 'mateship‘. Just as the Aishers, when wealthy men, would still in case of need step into the place of a workman laid low by illness or accident, so the drivers knew that they would not be abandoned and that, if need be, the man in overalls who turned up at midnight might be the transport manager.